I am an Assistant Professor in the School for International Studies and the Global Asia Program at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, and a member of the David Lam Center. My research and teaching focus on borders, (im)mobilities, sovereignty, Indigeneity, and place-making in the Himalaya and beyond, with particular attention to Indigenous and Tibetan refugee communities. I am also a member of Aruna Global South, a collective for emerging scholars and thinkers from, or with ties to, Asia and the Asian diaspora who are systematically marginalized in the spaces of knowledge production. Before joining SFU, I taught at Macalester College, Eckerd College, and the University of Colorado Boulder.

Education

PhD, Geography – University of Colorado Boulder

MA, Geography – Miami University

BA (Hons), Geography, Tourism, and GIS – St. Cloud State University

I grew up in the city of Patan, Nepal—or, as I often felt as a child, the city grew around me. I learned and relearned from the people who laboured in it and the alleys, old and new, through which they moved. Before I engaged with social theory, my education came from the social worlds of the city and my villages, where I began to see how identity shapes coexistence while also conditioning exclusion and othering.

Beyond South Asia, my life journeys as a settler—in a white, central Minnesotan town; in Latinx Pilsen in Chicago; and in Pan-Asian Flushing/Jackson Heights in Queens, NY—has shown me that social and political life is always more than textual. I take these experiences to heart as a visual geographer, grounding my ethnographic research in the textures of everyday life.

My research engages questions of sovereignty, Indigeneity, territory, ethnicity, power/violence, borders, (im)mobilites, and placemaking. I am interested in understanding how certain populations are rendered powerless through state mechanisms, and in the ways in which the (rendered) powerless navigate, counteract, and resist the dispossession of their bodies, land, and memory in their everyday lives. My research is centered around the question: How is sovereignty realized in the everyday? For this, I ethnographically engage with visual methodologies (photography and film) that create possibilities for different ways of seeing and knowing about being in the world.

Funded by a National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, my dissertation research, based on eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork, explored how sovereignty is perceived and understood as part of everyday life among Tibetan refugees and Ghunsali and Walung Indigenous communities in the Nepal/Tibet borderlands.

PUBLICATIONS

2023. Shrestha, Rupak. Territorial futures: On belonging, caste, and pedagogy. Dialogues in Human Geography. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206231186907

2022. Shrestha, Rupak. Affective borderings: Sovereignty and Tibetan refugee placemaking at the Nepal/China Borderlands. Political Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102764

2022. Shrestha, Rupak, and Jennifer Fluri. Geopolitics of security and surveillance in Nepal and Afghanistan: A comparative analysis. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544221115952

2021. Shrestha, Rupak, and Jennifer Fluri. Geopolitics of Humour and Development in Nepal and Afghanistan. In The Palgrave Handbook of Humour Research, edited by Elisabeth Vanderheiden and Claude-Hélène Mayer. Palgrave Macmillan. 189-203. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78280-1_10

2021. Shrestha, Rupak. Book Review of Geocultural Power: China's Quest to Revive the Silk Roads for the Twenty-First Century, by Tim Winter. Eurasian Geography and Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2021.1894966

Please get in touch if you need access to any of these publications. I am happy to share a complimentary copy with you.

BORDER & GEOPOLITICS | intimate social worlds |

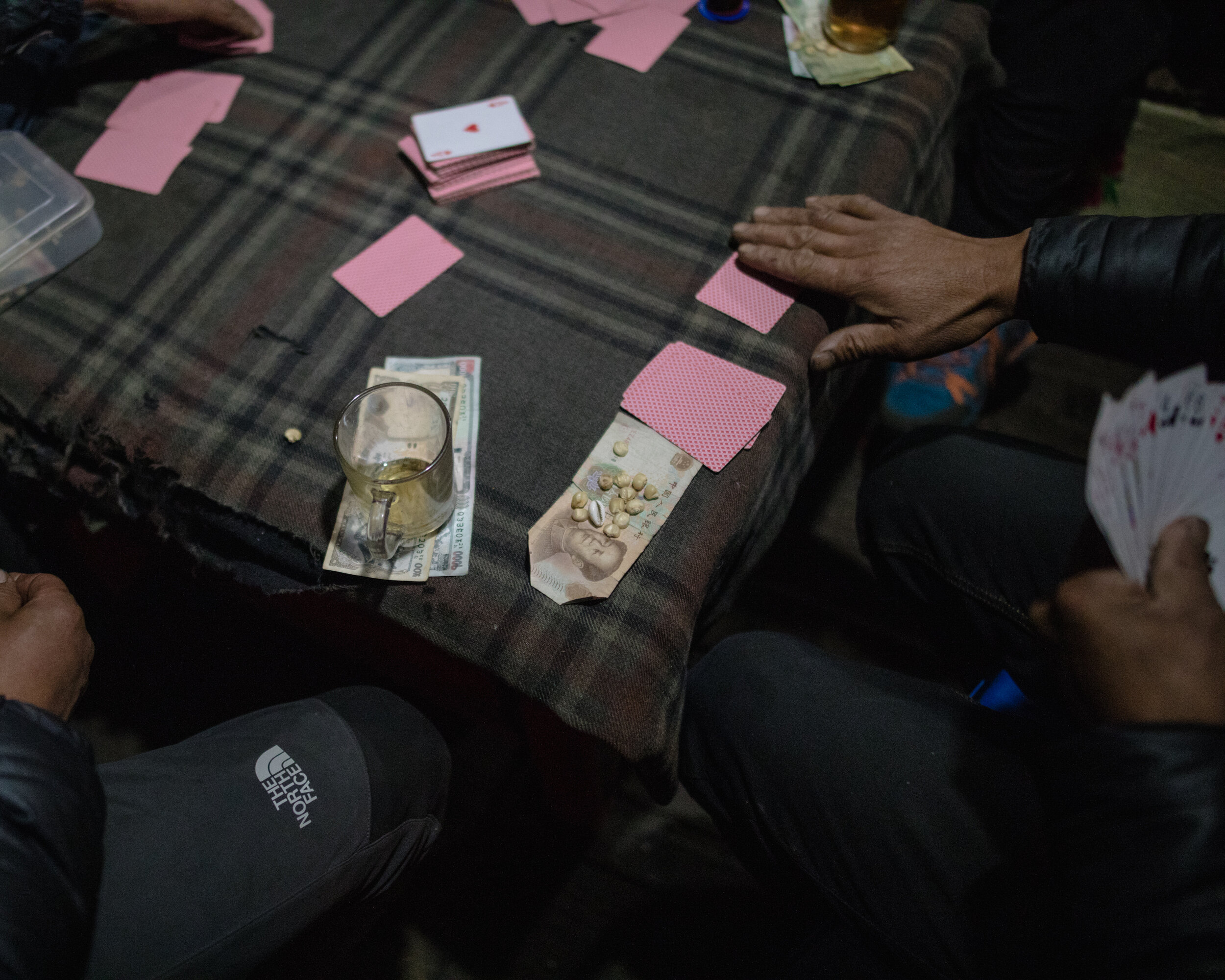

This work is based in the northeastern Nepal Himalaya (see map below). I draw from literature on intimacy geopolitics (Berlant 1998; Smith 2012; Barabantseva, Mhurchú, and Peterson 2019; Smith 2020) to argue that Tibetan refugees in Phale engage in strategic forms of intimacy with Walung Indigenous communities to effectively negotiate their place and political position to move from refugee to citizen. I show that Tibetan refugees’ and Walung peoples’ interactions are juxtaposed and conditioned by various manifestations of situational affect at the borderlands — for example at times through friendship, co-existence, and inter-marriage and at other times through competition and eavesdropping.

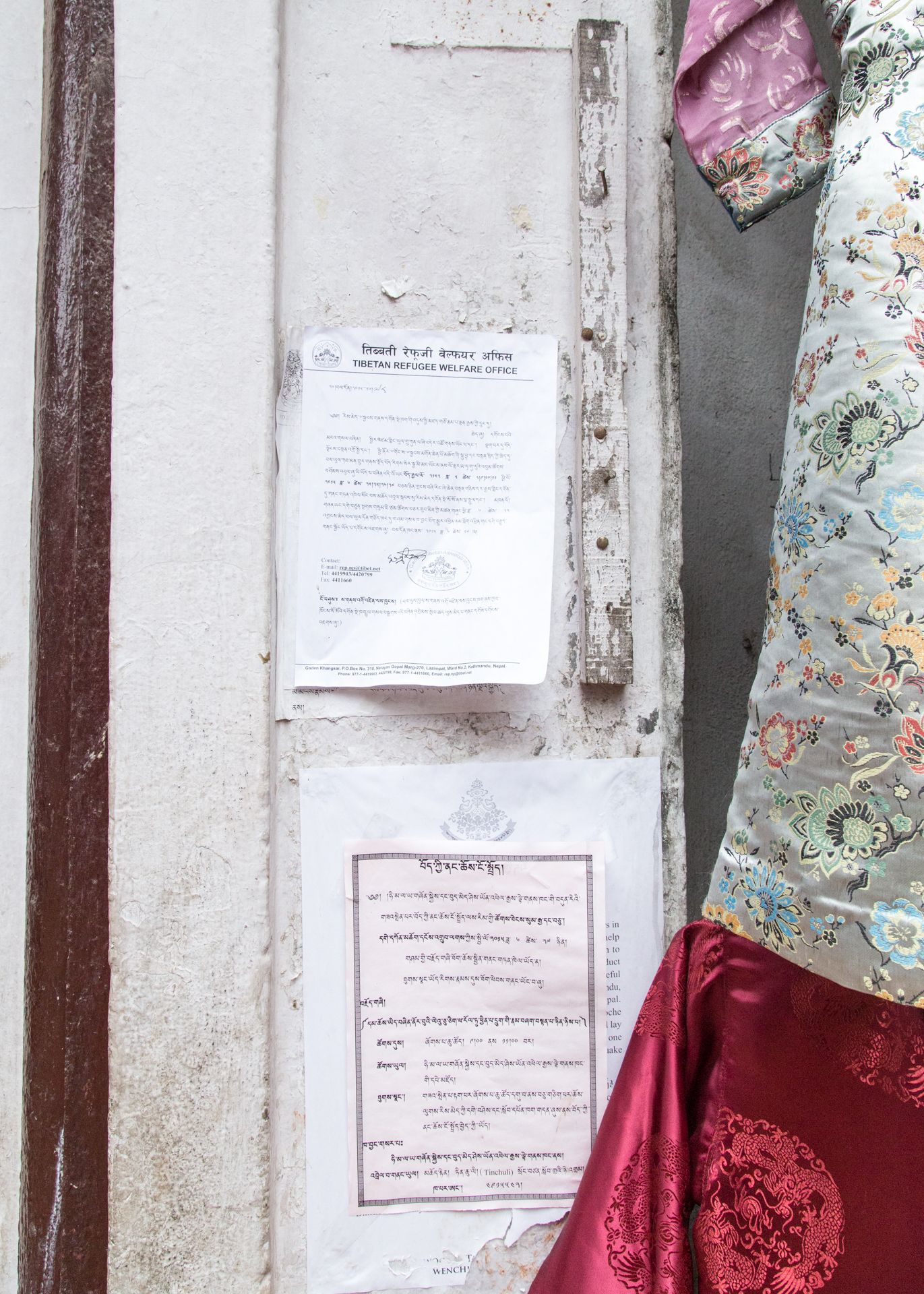

EVERYDAY SURVEILLANCE

I explore the intersections of aesthetic governmentality and everyday surveillance. I use the concepts of legibility (Scott 1998) and political visuality (Rose 2016) to argue that the nation/states make everyday mobilities legible and visible by way of surveillance, calculations, and distributions (Rancière 2004). Any dissensus or move away from aesthetic governmentality, is marked as illegal vis-à-vis its illegibility. In response, the state makes these acts of dissensus invisible through police action. This mode of governmentality is heightened for Tibetan refugees in Kathmandu.

BRICK | labor migration |

Due to uneven development practices, brick factory migrant laborers in Kathmandu are dispossessed from a life with social and economic possibilities. Before migration to the city, most migrants are lower-caste, landless peasants laboring in high-caste land holdings in western Nepal. They migrate to the city, although seasonally, to work as wage laborers in the brick industries that are spread throughout the southern and eastern belt of the Kathmandu Valley. Although this pattern does not seem anything new from what scholars in the Marxist tradition have analyzed before, such mobility — mostly conceived as economic — is gendered, and has political and social repurcussions. It dispossesses migrant bodies from a life with very little certainty into another that is infused with precarity.

By employing qualitative and visual methodologies, I track the everyday spatial, social, and political challenges faced by brick factory migrant laborers who are continuously pushed through economic and extra-economic means towards the periphery of urban spaces. I argue that dispossession and precarity maps itself in the bodies of migrants. Migrant mobilities draw a trajectory from the rural periphery to the precarious spaces of the urban periphery. There, they are structurally deprived of means to a future with possibilities. This life, without possibilities, is a life that is rendered apolitical in state calculations and asocial in an imagined society. But, migrants are humans nevertheless, with tremendous agency to counter these subjugations to imagine alternative yet distinct futures for themselves.

HOME-LAND AND HOME-LESSNESS

In Boulder, Colorado, my visual-ethnographic work examines the ruptures that homeland produces for United States military veterans who are homeless. Homeland is a powerful discourse in US military and security strategies. Imagined geographies of the homeland have produced the need to ensure and legitimize militarized security for the defense of the homeland — both within and beyond US borders. Walter, my research participant, is 65 years old, black, disabled, homeless, male, and a Vietnam veteran. Walter reveals the extent of violent racism while he was in Vietnam — a place where he had gone to evade the everyday racialized landscape of Mississippi: “some white Americans didn’t want me to come back, they shot me from both sides. One minute you are a friend, the other he wants me to come back in the box...I felt like a flower child, I didn’t want to go to war but I had to. Bottom line was, it was them or me. I couldn’t stay state-side”.

Walter’s narratives speak to the violent racism that rendered him as a vulnerable, racialized body both in the United States and in Vietnam. While he was protecting the homeland during times of war, his race simultaneously structured his possibilities over life and death in the shadow of empire.

US/MEXICO BORDERLANDS

the waves hit the shores - dismembered by a wall in the waters

the wind cried foul over its disjointing

the land suffocated in its metaled fractures

| se puede dividir la tierra, pero no se puede dividir el alma |